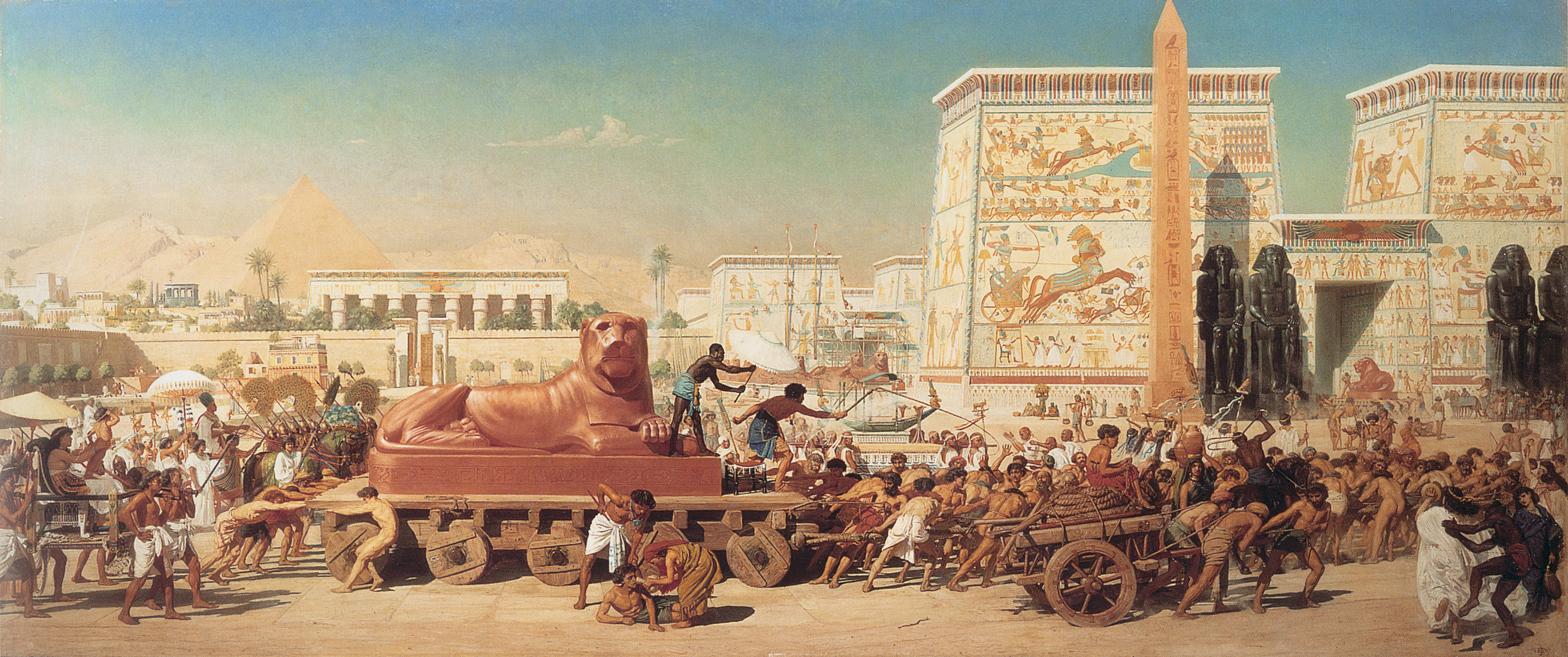

Plundering the Egyptians

Rethinking "Plundering the Egyptians": A Biblical-Theological Critique of a Misused Metaphor

The phrase "plundering the Egyptians," often used to justify Christian appropriation of secular or even heterodox thought, originates from Exodus 12:35–36. There, the people of Israel, at God’s explicit command, asked the Egyptians for silver, gold, and clothing. The Lord gave the Israelites favor in the eyes of the Egyptians, who freely gave these items. The result: "they plundered the Egyptians." Yet, a closer biblical-theological analysis reveals that this event, far from being a model for cultural assimilation or theological adaptation, serves instead as a theologically specific, God-ordained act of redemptive justice. Its appropriation as a metaphor for engaging secular or corrupted Christian thought is exegetically flawed, hermeneutically hazardous, and theologically dangerous.

I. Textual Clarity: The Nature of the "Plunder"

The Hebrew word translated "plunder" in Exodus 12:36 is nāṣal, which elsewhere carries the sense of "snatching," "delivering," or "rescuing." The Israelites did not seize Egypt’s treasures through violence or cunning but simply obeyed the Lord’s command to ask (sha’al). The Egyptians responded by freely giving their valuables, compelled by God’s providential favor (ḥēn) and the dread of His judgments. Thus, the "plundering" was an act of divine reversal and recompense, not an ideological strategy.

Importantly, this command was given on the eve of the Exodus (Exod 11:2–3), not after Israel’s liberation. They did not return to Egypt to extract wisdom or resources; they received what God directed them to ask for, in a one-time event tied to their deliverance from slavery. To universalize this act as a method for Christian engagement with culture is to impose a foreign logic upon the biblical narrative.

II. Redemptive Context: Justice and Worship

Theologically, this "plunder" was covenantal restitution. In Genesis 15:14, God promised Abram that his descendants would leave their affliction in Egypt "with great possessions." Exodus 12 fulfills this prophecy. The treasure received was not for indulgence but consecrated for worship. As seen in Exodus 25 and 35, much of this gold and silver was later freely given by the people to build the tabernacle—God's dwelling place among them.

The contrast between the faithful use of these materials in Exodus 35 and their idolatrous use in Exodus 32 (the golden calf) underscores a critical point: the material was neutral, but its use was either sanctified by obedience or corrupted by imagination. Cultural goods, like Egyptian gold, are not inherently redeemable; they must be reshaped according to God's revealed will. The tabernacle was built according to the divine pattern (Exod 25:9), not Egyptian aesthetics or philosophical blueprints.

III. Theological Misuse: From Augustine to Modernity

The metaphor of "plundering the Egyptians" took on a new life in Augustine’s De Doctrina Christiana, where he argued that Christians might appropriate truths from pagan philosophy, just as Israel took valuables from Egypt. This principle was later echoed by Reformers and Puritans who, while committed to sola Scriptura, also engaged with classical learning and literature. Indeed, the Puritans—especially in the English-speaking world—helped popularize and transmit this metaphor in the context of education and theological discourse.

However, this metaphorical extension obscures the sharp differences between the historical act in Exodus and the theological project it is used to support. The Israelites did not engage Egyptian religion, education, or philosophical systems. They received material goods as divinely ordered compensation. To reinterpret this as an endorsement of appropriating secular or heterodox ideologies (e.g., psychology, critical theory, or even the contemplative writings of Eugene Peterson) risks blurring the line between divine revelation and human speculation.

The error is not only in the method but in the implied authority. By claiming to "plunder" so-called truths from sources that are doctrinally flawed or spiritually misleading, Christians risk elevating error to the level of truth. To mine theological or philosophical insight from compromised sources is to risk clothing falsehood in the garments of divine wisdom. The gold of Egypt must not simply be repurposed—it must be melted, recast, and purified under the fire of God’s Word. Anything less risks creating modern golden calves—culturally adorned but spiritually bankrupt.

Scripture explicitly warns against uncritical assimilation. Paul reminds the Colossians: "See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition... and not according to Christ" (Col 2:8). He exalts the sufficiency of Christ, "in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge" (Col 2:3). The wisdom of the world is not neutral gold to be polished; it is folly apart from the fear of the Lord (Prov 1:7; 1 Cor 1:20).

Contrary to popular interpretations, Paul's sermon at the Areopagus in Acts 17 does not represent a case of “plundering the Egyptians.” While Paul quotes pagan poets (Acts 17:28), he does not affirm their systems or integrate their philosophies. Rather, he subverts them. He confronts their ignorance (v. 23), denies the legitimacy of their temples (v. 24), and calls them to repentance in light of Christ’s resurrection (vv. 30–31). The quotations serve not as endorsements but as points of redirection—Paul reclaims the language to expose the bankruptcy of their worldview and proclaim the Lordship of Christ. His method is proclamation, not appropriation.

IV. Israel’s Posture: Receivers, Not Strategists

The Israelites played no active role in manipulating their captors or strategizing a cultural extraction. Their role was purely responsive: they obeyed God's command to ask and received what was freely given. The real actor in the event is God Himself. He stirred the hearts of the Egyptians, fulfilled His promise to Abraham, and provided what was necessary for the future construction of His sanctuary.

This is no model for Christian cultural triumphalism. It is a moment of divine grace and justice. To transform it into a rationale for cultural engagement misunderstands both the text and the theological posture it teaches: humble obedience and receptive faith, not clever appropriation.

V. Christ and the True Tabernacle: Typology Fulfilled

The final flaw in the metaphor becomes clear when we consider its place within the redemptive-historical typology. The gold received from Egypt was used to build the tabernacle, the temporary dwelling of God among His people. But now, in the fullness of time, Christ has come as the true tabernacle: "And the Word became flesh and dwelt [tabernacled] among us" (John 1:14). In Him, God is fully present with His people, not through a gold-lined tent, but in incarnate grace and truth.

Moreover, Christ not only replaces the tabernacle—He fulfills all it represented. He is the High Priest, the sacrifice, and the mercy seat (Hebrews 9). Through His death and resurrection, He secures an eternal inheritance and opens access to the heavenly sanctuary. As the book of Hebrews argues, the tabernacle was a shadow; Christ is the substance (Heb 8:5; 9:24).

To continue seeking Egyptian gold for theological construction is to act as if Christ’s finished work is insufficient. It is to treat the true gold of Scripture as lacking and to imply that divine wisdom needs supplementation from human philosophy or mystical insight. But the gospel declares otherwise: "In Him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily, and you have been filled in Him" (Col 2:9–10).

VI. A Warning to the Lazy Exegete

In our present context, the misuse of this metaphor often reveals a deeper failure of theological diligence. The lazy exegete, unwilling to labor in the Word, will more readily turn to the culture for insights that seem practical or palatable. Instead of mining the depths of Scripture—the true gold refined by fire—such teachers adorn their theology with borrowed ornaments. They invoke cultural voices and compromised sources, not because they are convinced by their merit, but because they have neglected the harder task of faithful exegesis.

This borrowing is not bold engagement; it is theological sloth. It confuses relevance with reverence, utility with truth. The result is a body of teaching clothed in borrowed splendor, but hollow at its core. By contrast, the Apostle Paul instructs Timothy to rightly divide the word of truth (2 Tim 2:15), not to gather fragments of truth from unregenerate sources. The preacher or theologian must dig deep into the canon of Scripture, drawing forth what is pure, sufficient, and Christ-exalting.

VII. Conclusion: From Egypt to Zion

To rightly handle the Exodus narrative is to honor its redemptive shape and covenantal function. The so-called "plundering" was not a license for theological eclecticism, but a unique event demonstrating God's justice, providence, and preparation for worship. When we retell this event as a justification for borrowing secular theories or ideologies, we risk constructing golden calves rather than tabernacles—and in the light of the gospel, even tabernacles are obsolete.

The better model for cultural engagement is not Israel's departure from Egypt, but Paul's exhortation to "take every thought captive to obey Christ" (2 Cor 10:5). Ideas, like Egyptian gold, may be melted down, but only if they are reshaped entirely by God's Word and used solely for His glory. We are not cultural magpies scavenging for shiny objects; we are stewards of revealed truth, called to discern, test, and submit all things to the Lordship of Christ.

The tabernacle has already been built—not by human hands, but by the eternal wisdom of God in Christ (Heb 9:11). Let us not return to Egypt to seek what we have already been given in Christ alone.