Covenantal Rest

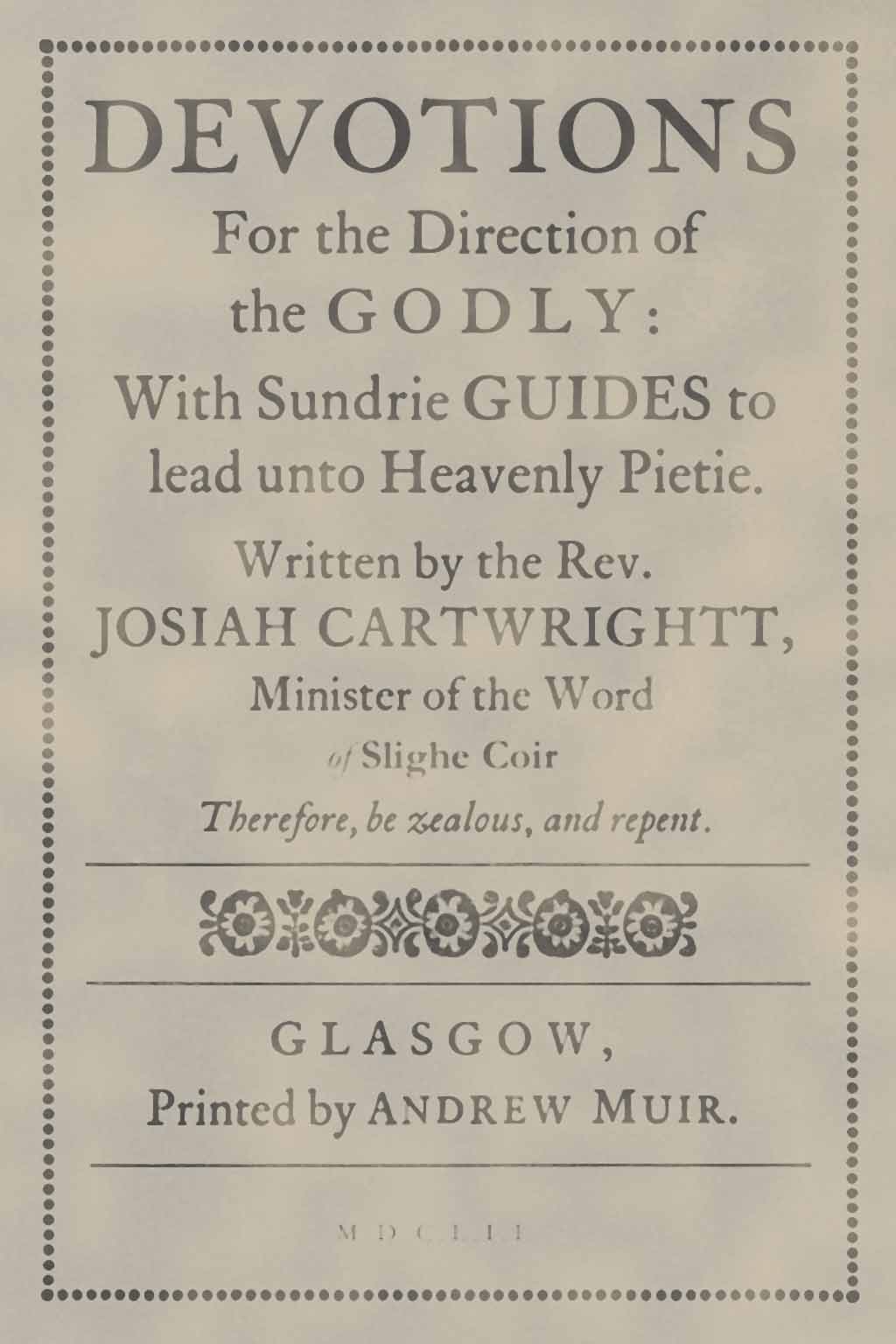

A devotion from the Puritan minister, the Rev. Josiah Cartwright.

Covenantal Rest

“Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all the host of them. And on the seventh day God ended His work which He had made; and He rested on the seventh day from all His work which He had made. And God blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it.” — Genesis 2 : 1–3

God’s “rest” is not the easing of fatigue but the expression

of divine completeness. To “bless” and “sanctify” the seventh day means that He

consecrated time itself as a meeting place between Creator and creature. Before

any temple stood, time became the first sanctuary. God wrote communion into the

calendar.

“All the host of them” widens our vision: the heavens with

their starry ranks, the earth with every kind of life, and—unseen but no less

real—the angelic hosts who serve and praise. Paul affirms this scope: “By

Him were all things created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible,

whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities” (Col 1 : 16). Every

order of being, material and spiritual, stands arrayed before its King.

Creation ends not in exhaustion but in worshipful order; it begins already as

covenantal fellowship offered to the creature.

The Great Completion

All the “and God said” commands of chapter 1 march toward this stillness. The Father’s decree reaches its end; the Son, the eternal Word, executes it flawlessly; the Spirit, who hovered over the waters, now fills the finished cosmos. The Triune God reveals His wisdom and goodness without change or new affection. His rest is His immutable satisfaction—the harmony of creation with His eternal will.

That perfection is covenantal: the world is complete for fellowship. God’s work is perfect not only because nothing is lacking materially, but because everything stands ready for relationship. The Maker fashions a dwelling fit for communion, and His rest proclaims that creation is suited for His presence. The first Sabbath therefore signals covenant rest—God enthroned among His works, inviting His image-bearer to share His peace.

The Covenant of Creation

Here we discern the first covenant—the covenant of creation, sometimes called the covenant of life. God pledges Himself to the man and woman as Lord and Benefactor; they owe Him trustful obedience and grateful worship. The Sabbath is the sign of this relationship. Even before law or sacrifice, rest is the appointed seal of fellowship.

To rest with God is to live rightly under His rule. Work is holy, yet it points toward worship; labour ends in communion. The weekly rhythm preaches: “You are not sustained by your toil, but by My faithfulness.”

Exodus 31 : 16–17 later makes this covenantal link explicit: “The children of Israel shall keep the Sabbath… for it is a sign between Me and the children of Israel forever; for in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day He rested and was refreshed.” What was instituted at creation becomes codified under Moses: rest as sign of belonging. The Sabbath marks a people who live by God’s provision, not their own productivity.

Thus covenantal rest is the creature’s weekly confession of grace. To cease from labour is to trust the covenant Lord. When Adam fell, he shattered that rest before he plucked the fruit. His discontent with divine sufficiency broke the covenant of life. Since then, humanity’s restlessness has been its own testimony of covenant breach—cities built without peace, hearts unquiet until grace restores them.

The Covenant of Grace

The seventh day also looks forward to a second covenant, the covenant of grace. Israel’s Sabbath, joined now to redemption from Egypt, preached that the same God who created also delivers. The sign of creation becomes the sign of salvation: “Remember that you were slaves in Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out… therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the Sabbath day.” (Deut 5 : 15) Their rest was covenantal again—grounded in mercy, not merit.

Yet even this was provisional. Every Sabbath sunset declared that the true rest was still to come. The prophets called Israel back to delight in the Lord (Isa 58 : 13–14), and the Psalms yearned for the day when God’s people would enter His rest fully (Ps 95 : 11). That promise awaited the coming of the Son, the Lord of the Sabbath.

When Christ cried, “It is finished,” He brought to fulfilment the covenant of rest begun in Genesis and renewed at Sinai. His death and resurrection opened the everlasting Sabbath of grace. The covenant of creation, broken by Adam, is remade through the obedience of the Second Adam. In Him, covenantal rest is not merely commanded but granted. He is Himself our Sabbath, our dwelling with God. As Hebrews 4 : 3 declares, “We who have believed do enter that rest.”

This present participation is the heartbeat of the new covenant. The believer rests now in justification, resting from self-righteous toil. Yet this rest still looks forward to consummation—the day when faith will yield to sight, and covenant fellowship will be full and unbroken. Thus covenantal rest is both already and not yet: already enjoyed in Christ, not yet perfected in glory.

The Rest of God and the Peace of His People

The rest of God is the model and source of the rest of His people. The Father rests as sovereign, His decree accomplished; the Son rests as Mediator, His redeeming work complete; the Spirit rests by indwelling, applying peace to the heart of the redeemed. The believer’s Sabbath, therefore, is participation in this triune fellowship—the creature drawn into the Creator’s serenity.

Covenantal rest is no mere rhythm of body but a communion of soul. To rest is to return to covenant trust, to recognise that providence governs even when our hands are still. Each Lord’s Day is a covenant renewal: God calls His people to remember His works and to delight in His Son. Worship is the weekly handshake of grace.

The Bride’s Covenant Rest

The covenantal design reaches further. The Sabbath of Genesis prefigures the marriage covenant between the Son and His Church. When Adam awoke to Eve, he beheld in her God’s gift of companionship; when Christ rose from the tomb, He beheld in the redeemed the Bride prepared for Him. The Father’s satisfaction in His finished creation thus already contained the foresight of this union. All of history moves toward that great Sabbath when the Bride will enter the rest of her Husband and the covenant of grace will blossom into the covenant of glory.

Revelation 21–22 pictures that day as the true Sabbath: no night there, for rest and worship are one. The covenantal rest of the Church is the eternal dwelling of God with His people—what the seventh day signified and the Lord’s Day now foretastes.

A Rhythm for Worship and Work

Because God’s covenantal rest is perfect and secure, the Christian may labour without anxiety and rest without guilt. The Sabbath pattern remains a moral mercy. To cease is to confess. Each pause proclaims that the covenant Lord keeps His promises, sustains His world, and completes His work. In this rhythm of worship and work, grace orders time. The believer’s week begins with rest, not ends with it—because redemption, not effort, defines the covenant.

Our Sabbath Foretaste

When you lay down your labour, remember that the Father’s rest is sovereignty, the Son’s rest is rule, and the Spirit’s rest is indwelling peace. Our quiet hours are shadows of that triune calm. We keep the day because He keeps us. And as we wait, we look toward that morning when covenant and creation will meet in everlasting harmony—when the Son rejoices, unchanging yet ever blessed, over His perfected Bride, and the whole host of heaven and earth joins the song of rest.

Then covenantal rest, first whispered in Eden, will fill the new Jerusalem like air: no more toil, no more curse, no more night—only the unbroken Sabbath of God.